Unlike many young Singaporeans, Luretta Seah had the opportunity to befriend a construction worker from India.

“He’s my dad’s right-hand man,” says the 19-year-old. She’s referring to Mr Subramaniyan Vallaichamy, also affectionately called Uncle Sami, who’s worked with her father in the oil industry for 20 years.

Outside of work, Luretta’s father and Uncle Sami enjoy flying kites at Marina Barrage together, especially during long weekends or over the Chinese New Year break. Other family members would join the fun sometimes.

Luretta also recalls how Uncle Sami once helped her fix a broken bar at the gymnasium she was training at.

When foreign worker dormitories emerged as a hotbed for Covid-19 infections in April, Luretta was worried about Uncle Sami, who had to be quarantined in his dorm room. Thankfully, he’s not infected.

Watch: Luretta Seah on Uncle Sami

Two Worlds Apart

Luretta’s family is an outlier. Most Singaporeans wouldn’t know a construction worker on a first-name basis. Even if they do, many wouldn’t have bothered to develop friendships with this community of migrant workers.

Some have even gone to great lengths to avoid having them in their backyard. Back in 2008, more than 1,400 Serangoon Gardens residents petitioned against the building of a foreign workers’ dormitory in their estate, citing concerns about crimes, noise pollution, traffic congestion and potential drop in their property prices. The dormitory was built anyway, but with a separate access road to minimise “disruption” to residents’ lives.

Most of the large purpose-built foreign worker dormitories are located at the outer reaches of Singapore now.

These licensed dorms, together with the temporary quarters erected on construction sites, are where most foreign construction workers like Uncle Sami call home.

As work permit holders, foreign construction workers aren’t allowed to rent a room in HDB flats unless they are Malaysian citizens.

Out of sight, out of mind. The workers’ welfare, as a result, is rarely on Singaporeans’ radar.

Turning Point

The Covid-19 pandemic marks a turning point. Foreign workers’ plight came to the fore when huge Covid-19 clusters started emerging in their dormitories.

Many believe that their cramped living condition, with many workers sharing a room and common toilets, has made it easier for the virus to spread fast.

Photo Credit: Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME)

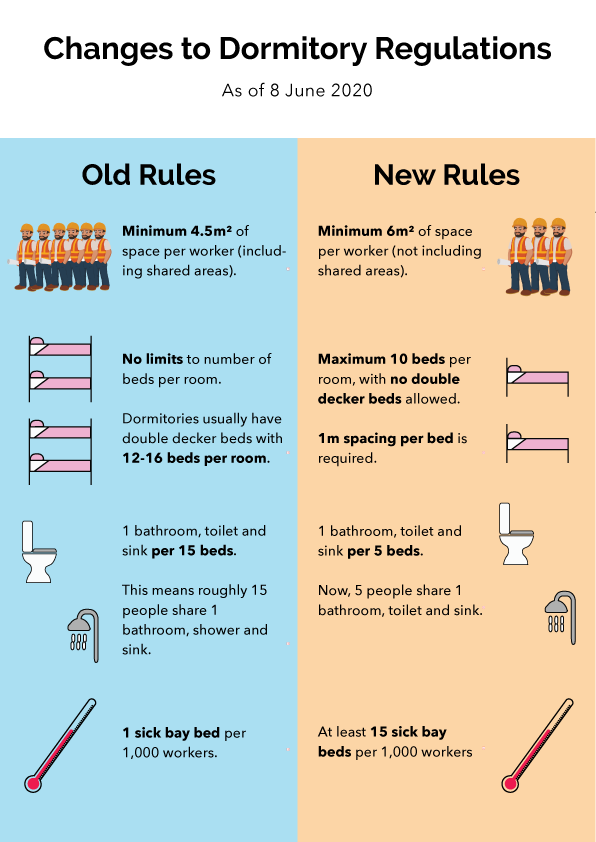

Before Covid-19, dorm operators like the public-listed Centurion Corporation used to allow up to 12 workers in one apartment while meeting past regulatory requirements such as providing 4.5sqm per resident within the apartment.

According to a Centurion spokesperson, employers typically rent entire apartments from them to house their foreign workers, paying between $250 and $300 per worker per month. The more cost-conscious employers would usually try to accommodate as many workers as allowed in each apartment while following regulatory limit requirements.

But this is changing as dorm operators are compelled to reduce density in their rooms to minimise public health risks.

“In the long run, Centurion will work very closely with the government to meet the regulations,” says the Centurion spokesperson. “Compliance with all these regulations is really important; it’s always our priority.”

Changing Perceptions

This Covid-19 outbreak has made more Singaporeans more empathetic and grateful towards migrant workers, particularly those who have been toiling away in dangerous, unglamorous, but essential jobs.

During the circuit breaker period, many came together to lend a helping hand to the workers.

Sew Love SG, an initiative started by Cheng Li Hui, MP for the Tampines East ward, saw many residents of Tampines sewing handmade masks for foreign workers.

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) like Citizen Adventures, Migrant x Me and Singapore Migrant Friends came together as Covid Migrant Support Coalition and raised funds to buy meals and daily necessities for affected workers. They also designed activities and content to engage workers who were quarantined in their dorms.

Better Housing

Minister for Manpower Josephine Teo said there are about 200,000 migrant workers who live in 43 dormitories in Singapore. The numbers came as a shock to many who’re previously clueless about the high-density living in mega dorms.

Various individuals and groups have since proposed different models of housing that promise more living space for each worker.

The government has also developed new specifications for the new purpose-built dormitories that will be built over the new few years.

Infographic by Dexter Lok

Professor Eugene Tan, an Associate Professor of Law at Singapore Management University, agrees that it’s time to reimagine and redesign foreign workers’ housing.

“Singapore does not have a choice but to reduce the density of all types of foreign workers’ housing,” says Prof Tan.

Additional Costs

The additional costs that come with improved housing will have to be “shared equitably between the government, the employers, dorm operators, businesses, and consumers”, says Prof Tan. But moving forward, he says employers should bear more of the costs. After all, taxpayers have already paid for the treatment of infected workers, the mandatory testing of all dorm residents and other costs associated with re-housing them in alternative sites.

“We cannot continue to have the gains largely privatised with the costs largely socialised.”

He adds that the bigger question to ask is not whether we can afford to reduce dormitory density, but whether we are determined to do so.

While these suggestions are welcomed, some NGO representatives have raised concerns that the additional costs might be passed on to the workers themselves.

“The employer would pass on these costs to the workers one way or another. The workers do not have any option, due to the imbalance of power between them and their employer,” a representative from the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME) says.

HOME added that although the new living quarters can be built, it’s no guarantee that workers will enjoy a better standard of living if the dorm operators are not closely monitored to make sure that the rules are followed.

HOME also believes in integrating foreign workers in our society.

“Our society needs to have the same expectations … for housing these sons and fathers as we would our own. Continued segregation will not achieve this,” HOME’s representative says.

Ms Deborah Fordyce, president of Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2), says that the upcoming dormitories built under the new regulations “are not necessarily a good starting point to improve the welfare of the migrant workers”.

Rather, TWC2 is more concerned about issues such as the non-payment of workers’ salaries, lack of proper medical treatment for injured workers and the exorbitant fees that workers have to pay recruitment agencies in order to land a job.

TWC2 has long called for legal reforms to protect the rights of migrant workers and feels that this warrants more urgent attention.

Legal reforms will take time. Better dorms won’t be built overnight. However, the public can certainly show more respect and gratitude towards our migrant workers – right now.

“Migrant workers have played an indispensable role in building our nation – their well-being should be a matter that is of national concern,” says HOME.

Edited by: Eunice Tan

Proofread by: Christel Yan