Much like peers of my age, I grew up never getting to know any migrant workers personally.

All I heard were classic stereotypes: foreign construction workers are dirty. Filipino helpers tend to steal while Indonesian maids are all well-versed in witchcraft. These stereotypes are outright damaging. As much as I can, I try not to let them colour the way I see migrant workers, who are here in Singapore to earn an honest living.

Yet, I admit that for a long time, I was like most Singaporeans who hardly cared for the welfare of migrant workers.

Re-examining Perceptions

That changed in March 2020 – when the migrant worker community came into the spotlight after the massive outbreak of Covid-19 cases in their dormitories.

I remember being outraged. Why were our migrant workers living in such poor, cramped conditions? Had we not learnt our lessons from previous disease outbreaks? I wonder if we really don’t owe them an apology – just because none of them demanded it as former Manpower Minister Josephine said in Parliament.

Social distancing is a privilege.

— ಶರಣ DR JAGADISH J HIREMATH (@Kaalateetham) March 23, 2020

It means you live in a house large enough to practise it.

Hand washing is a privilege too. It means you have access to running water.

Hand sanitisers are a privilege. It means you have money to buy them.

While many of us grumble about the various restrictions and lockdown measures, we should also be keenly aware that being able to work or study from a clean and safe home, being able to practise social distancing in public places are all privileges that migrant workers have no access to.

Think about how they have to share a small, damp, poorly-ventilated dorm room with 10 to 20 other co-workers. Think about how 20 to 30 of them have to share a bathroom and toilet. Think about how they have been cooped up in their dorms for the last 20 months or so despite having been vaccinated and are frequently tested – before a small batch of them were finally allowed to visit Little India in a recent pilot scheme.

I feel bad for their plight. I also feel bad for my ignorance towards the workers who build our homes, offices, attractions, roads, trains and many more. I should get to know them better beyond the simplistic stereotypes I had grown up hearing about.

Discovering Migrant Literature

That’s when I roped in my teammates Joey and Sarah to work with me on a feature that centred on whether we’ve done enough for migrant workers for this publication.

During our research last year, I came across the renowned migrant poet Mohammed Mukul Hossine and his poetry collection, Me Migrant. We had originally intended to reach out to him as a potential interviewee for our article as he is fluent in English.

Hossine’s anthology took me by surprise. It has not occurred to me that a migrant worker would have been so active in our local literary space, much less get published professionally.

I was also pleasantly surprised to find out that Hossine was not the only published migrant writer in Singapore.

A poem that I especially enjoyed was “Execution” by Belal Hassan, a Bangladeshi migrant poet who currently works at a manufacturing factory. This poem was a submission for the Call and Response 2 anthology.

“Execution” by Belal Hassan (Excerpts)

I’m hanging from the gallows

an adorable failure

the prayer of death

I’m hanging with the first sun of the morning

Here

I’m not alive,

not even dead;

but in the crime of survival

I’m hanging from the gallows

I’m just waiting for instructions.

Hassan’s piece speaks strongly about the suffocation felt by a migrant worker; the stringent restrictions on their movement leaves him a helpless man who has lost all sense of freedom.

I read this piece with a heavy heart. I simply cannot fathom living a life defined only by regulations and instructions.

Emerging Literary Subgenre

Beyond these individual writers and projects, I learn that the works of our migrant writers – termed ‘migrant literature’ – is in fact an up-and-coming literary subgenre in the local literary scene.

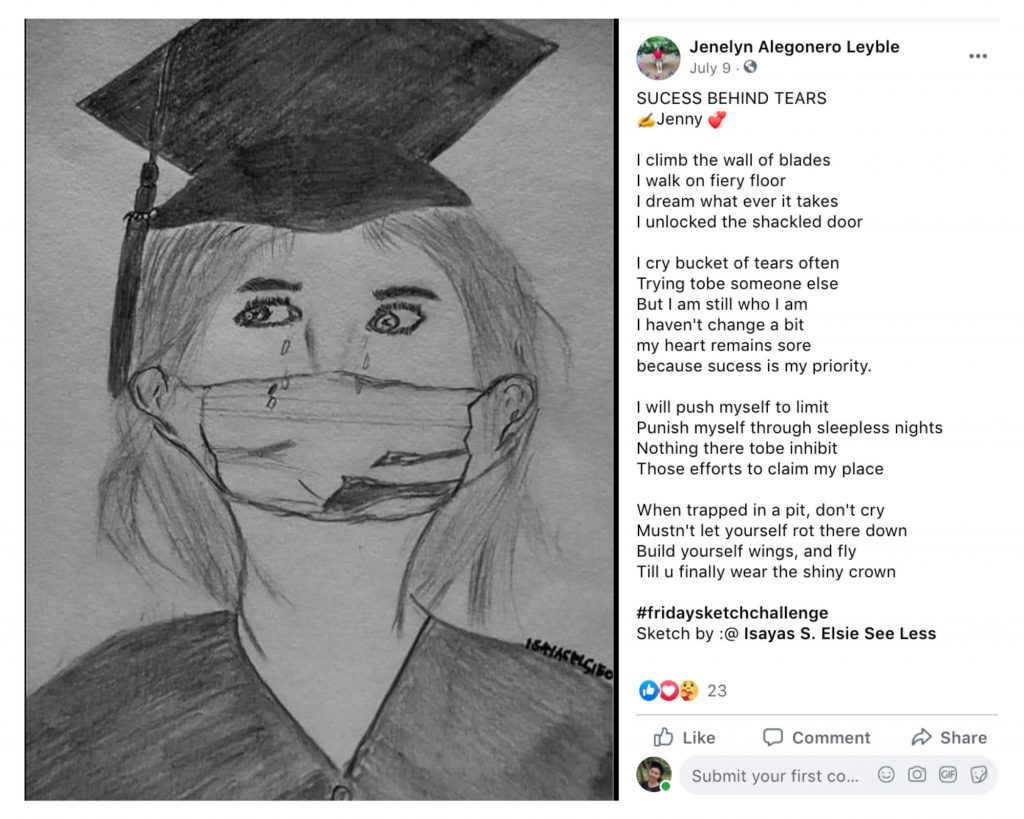

This subgenre was born from literary spaces like the Migrant Writers of Singapore, a Facebook group which hosts regular open mics and literary events to bring together wonderful migrant talents, and Birds Migrant Theatre, a theatre company formed by migrant workers hailing from Indonesia, Bangladesh and The Philippines.

Editor of Call and Response 2 Poh Yong Han explains that these migrant literary spaces (and migrant art in general) began to proliferate after the success of the first Migrant Worker Poetry Competition in 2013.

Since then, independent publishers like Math Paper Press, Ethos Books and Landmark Books have been providing platforms for migrant writers to share their stories with the world.

Closing Thoughts

Reading migrant literature hasn’t just helped me understand the migrant community at a deeper level. It’s also made me reflect more on the privileges that I enjoy just by the virtue of my citizenship.

I hope that as a society, we can consider reexamining our own perspectives on our migrant workers. Perhaps as a start, we could be more open to understanding our migrant workers on a deeper, more personal level. By hearing their stories and their struggles, we can create a better society which embraces our migrant workers as well-respected human beings.

At the time of writing, Dexter Lok was a marketing intern at Ethos Books. This article is solely meant to express his appreciation for the migrant literature subgenre and does not contain any partnerships with the publishing house.