By Farah Hazirah and Gordon Ng

Yayoi Kusama is a diminutive 88-year-old woman and possibly the world’s most famous living artist. Just take a look at the roughly 384,000 posts on Instagram tagged with her name.

This year, for the first time in Southeast Asia, the National Gallery Singapore will be hosting a major retrospective of Yayoi Kusama’s masterpieces from Jun 9 to Sep 3. Named after a painting from her most recent and ongoing My Eternal Soul series, Yayoi Kusama: Life is the Heart of a Rainbow will present 120 works from seven decades. Visitors will also be treated to new and never-before-seen works by the artist.

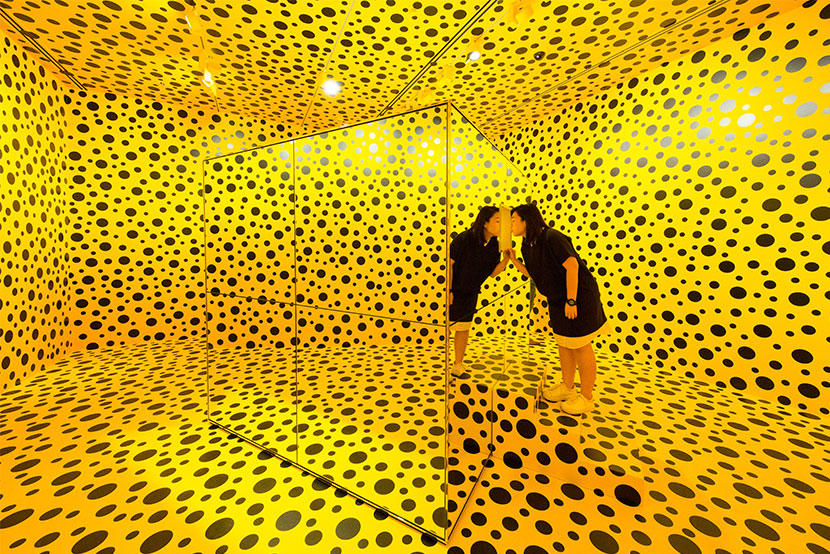

Some of Kusama’s key works that will be exhibited at the National Gallery of Singapore includes No. A (1959), an Infinity Net painting composed of small tight loops painted repeatedly over a plain ground, Infinity Mirrored Room – Gleaming Lights of the Souls (2008), an infinity mirror room made up of repetitions of nets and dots, and With All My Love For The Tulips, I Pray Forever (2013-2017), her first-ever room installation full of repeated forms and images, such as phallic objects and dots.

Even after years of being a working artist, her relevance in the art scene has not waned and is even gaining more popularity among Singaporeans, especially millennials.

A History of the Artist

To understand Kusama’s work, it is important to have a handle on her history and its effects on her art.

For starters, Kusama was born in Japan in 1929 to a family of merchants who disapproved of their daughter’s passion for art. At the age of 10, she started experiencing vivid hallucinations that would go on to influence nearly every aspect of her work.

At 19, she enrolled in a Japanese art school and studied traditional forms of painting before quickly becoming bored and frustrated with its limitations. Instead, interested in the avant-garde movement that was flourishing in Europe and America, she left for Seattle at age 27. Within a year, she had written a letter to modernist pioneer Georgia O’Keeffe and received a reply that encouraged Kusama to make the move to the faster-paced New York City.

In New York, Kusama rapidly gained a name as an avant-gardist, though American sculptor Claes Oldenburg, who had lived in the same building with Kusama in the 60s, has been quoted saying “she didn’t have the kind of mind that identified with movements” and that she “just went her own way”.

It was the ’60s, and New York proved fertile ground for Kusama to explore other mediums of art: installations, performance-type events she dubbed ‘happenings’, videos and large-scale paintings. Events like the Vietnam War added a tinge of political protest to Kusama’s work; her rising fame and influence placed her artworks alongside names like Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol.

Amid international fame and notoriety, she returned to Japan in 1973 following the death of her partner Joseph Cornell and her own worsening health. In 1975, she was checked into the Seiwa Hospital for the Mentally Ill in Tokyo and has been a permanent resident since. Two years after being institutionalized, she opened a studio just across the road from the hospital and continues to work there.

Yayoi Kusama’s Influence

Today, Kusama is a legend in the art world. Her influence has gone beyond the exclusive world of gallerists and wealthy buyers and entered the common consciousness of the everyman.

While living in New York in the 1960s, Kusama began to show extensively in Europe, with her fame and notoriety exploding as a result of her Narcissus Garden piece at the Venice Biennale in 1966. There, she began personally peddling the silver balls that literally made up her artwork, before being stopped by the Biennale authorities. They thought it was unacceptable that Kusama would sell art as if it were a product. The momentous exhibition brought the artist considerable international press and exposure, positioning her as a reactionary to the consumer-facing side of the art world.

This sort of attitude has influenced artists, including most notably Damien Hirst and Andy Warhol. Warhol, the pop-art master, who has been accused by Kusama of copying her, and while disputable, it is almost impossible to divorce the themes of industrial reproduction that Kusama first began exploring with the purpose-made and easily repeated motifs in her work.

Repeated Themes

Since the tender age of 10, Kusama’s work has covered a broad spectrum of thematic obsessions: repetition, polka dots, sex, feminism, self-obliteration, and commercialism. Many of these stemmed from her hallucinations, and she would go on to use drawing as a therapeutic method to seek solace and overcome the anxiety that haunted her.

Kusama gained the title of the ‘Polka Dot Princess’ because of her artistic obsession with dots and her way of using them as a repetitive motif. The use of such techniques can be inferred as a means of exploring the concept of infinity and to negate the self.

Kusama, however, merely offered that “polka dots are fabulous” in an interview with the Associated Press in 2012, in the article Artist Kusama sees the world in dots.

One of the turning points in Kusama’s career was her Infinity Net series. The paintings, which depicted repeated networks of dots and semicircles, are still some of her most celebrated and demonstrates the artist’s use of repetition and polka dots. An early piece, titled No. F (1959) marked a shift in her work from painting singular abstract forms to the insistent and repetitive style that has since become her signature.

Ika Zahirah, 18, a final-year student from Singapore Polytechnic and a fan of Kusama’s work said that the work endeared her to the artist because “simple things like dots can be made into an artwork that’s very compelling and very intriguing.”

The monochromatic shapes formed a visual illusion of dizziness and hypnotism that seem to invite the viewer into Kusama’s world of hallucinations that the artist once described as “visual and aural” that involved violets with human-like facial expressions speaking to her. She once described it as a canvas “without beginning, end, or center”, and it represented a forward-looking style for the schools of Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism in New York.

Kusama’s work has also been called feminist. Critics have debated the source of Kusama’s sentiments, but Mr Russell Storer, who is in his mid-50s, one of the curators of the National Gallery’s exhibition, said: “It’s all about fear. The fear of sex, the consumption of sex or being consumed by someone else.”

One of Kusama’s first works to be exhibited dates back to 1953. The Woman (1953) was a blob with dots in the center floating against a black backdrop with red spikes surrounding it.

It seemed to represent “vaginal imagery” to Ms Beverley Sng, 26, a legal secretary and first-time viewer of Kusama’s work at the National Gallery’s exhibition. Kusama is also asexual, and it might be inferred that her confrontations with femininity and masculinity are derived from her aversion to, and fear of, sex, according to Decomposition: Post-disciplinary Performance by Susan Leigh Foster, Philip Brett, Sue-Ellen Case.

One of the most commonly recurring words used to describe Kusama’s work is ‘obliteration’, a concept of removing the individual self through overwhelming repetition.

This was evident in her 1965 work Infinity Mirror Room, which placed viewers in a room covered wall to ceiling with mirrors and housing LED light displays. In that dizzying setting, Kusama aimed to obliterate the viewer’s sense of self. In an interview with Bomb magazine, the artist defined it as “[returning] to the infinite universe” through “obliterating one’s individual self”.

One of the curators, Ms Adele Tan, who is in her 40s, noted that these installations can “physically make you want to throw up” and “make your skin crawl” as they are “psychosomatic phobias that you resist whether you’re conscious of it or not”.

Kusama created a greater impact when French fashion brand Louis Vuitton’s then creative director Marc Jacobs collaborated with the artist on the 2012 collection and Kusama’s polka dots found its way onto a line of bags, accessories, and clothing.

Yee Tian Xin Sandra, 19, a final-year student from Temasek Polytechnic and first-time visitor of Kusama’s work, said: “I got to know of [Yayoi Kusama] after seeing articles about her works, especially the fashion collaboration she had with Marc Jacobs and that got me interested in her artwork.”

Her ever-changing themes throughout the years have made her work relevant. In this era, her works hold “Instagrammable” value, as visitors and those who appreciate her art flood their timelines with Kusama’s most prominent works, such as Pumpkin (1994), Obliteration Room (2002-present) and Infinity Mirrored Room – The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away (2016).

Mr Reuben Keehan, who is in his 40s, and a curator with the Queensland Art Gallery who was involved in the National Gallery’s exhibition, said: “I think it’s relevant partly because it’s so popular … exhibitions with Kusama in it cause people to ask ‘why is she so popular’ or ‘why is she doing this’, and the very fact these questions are asked is a critical function of the exhibition [for the public].”