It started with her heart racing and thumping. Then came the feeling of adrenaline rushing through her veins. A shortness of breath followed, accompanied by a sharp pain in her chest. Within seconds, tingling sensations coursed through her whole body. She could move but she felt numb all over. She wondered what her body was up to, and started panicking about the fact that she was panicking.

That was how 35-year-old Elrica Tanu described her first panic attack in 2016. At first, she thought it was a heart attack.

The increased frequency of such panic attacks led her to a doctor’s visit that changed her life.

Photo Credit: Elrica Tanu

After consulting two doctors, the award-winning Mediacorp documentary producer found out the underlying cause of her increasingly frequent bouts of anxiety attacks. She was diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s Disease (PD).

“My first thought was that, as far as I know, Parkinson’s is an incurable disease, so it meant that I will not get better,” says Ms Tanu.

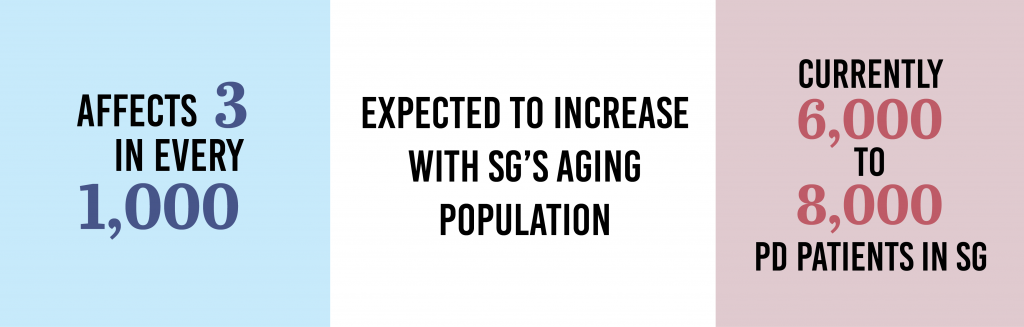

PD is a neurological disorder that progressively worsens. It’s the second most common neurodegenerative disease in Singapore after Alzheimer’s Disease.

While PD is more commonly diagnosed among those above 50 years old, it can also affect younger people in their 20s and 30s. According to Professor Louis Tan, a Senior Consultant Neurologist and Deputy Director for Research at the National Neuroscience Institute (NNI), only 10% or less of PD patients have symptoms before 40 years old.

For Ms Tanu, her symptoms first appeared when she was 30. Besides the panic attacks, she also noticed a slight tremor in her hand when she was writing or trying to apply mascara on her lashes.

“My doctor told me that [it] could be two things – a psychological or neurological problem… So I went to see a psychologist and a neurologist. The neurologist told me that I have Parkinson’s,” Ms Tanu said.

According to PD clinical guidelines by the Ministry of Health, PD symptoms can be motor and non-motor related. Motor ones involve involuntary tremors, muscle stiffness and slowed movements. Non-motor symptoms such as depression and dementia tend to be under-treated.

Every PD patient may experience different symptoms. Ms Tanu experiences tremors, muscle rigidity and slowed movements, some of the most common signs of PD. As PD is degenerative, her symptoms have become more pronounced over the years.

“The extreme form of rigidity is when I cannot move at all, it’s like I’m a block of statue.”

Medication and Treatment

According to the Parkinson’s Foundation, there is no cure for the illness as of yet.

The exact cause of PD is unknown, but Professor Tan says that people with Parkinson’s (PwPs) under 50 years old are “more likely to have a genetic contribution to their illness”.

Studies have shown that genetic mutation in 65% of people under 20 years old and 32% of people between 20 and 30 years old was believed to increase the risk of PD. However, some people with these genes may not develop PD.

Among PwPs, there’s the commonality of damaged substantia nigra neurons in the brain that causes dopamine deficiency. Dopamine plays a role in neurological and physical functions, making it important for our ability to think, move and pay attention.

Medication and various therapies are present to help slow down the progression of the illness and are recommended based on an individual’s situation.

For the first three years after being diagnosed, Ms Tanu took medication that would last 24 hours. When her condition worsened, she switched to three hourly medications that come with side effects such as sleep problems. Both medications help with the production or replacement of dopamine in the brain.

“I can’t sleep more than 2 to 3 hours at any one stretch of time and it’s hard to fall back asleep when I’m up.”

She says that it’s actually kind of a “catch-22 [no solution as factors conflict with each other] situation” because sleep actually repairs cell damage. “But the medication makes it hard for you to sleep for more than 8 hours,” she explains.

Within the first few hours of taking her medication, her symptoms are significantly controlled and she “isn’t hampered by [her] difficulty in moving”. This period is labelled as an “on” time. As the medication wears off and her symptoms return to usual, it creates an “off” time. Exercising frequently helps her to prolong “on” periods.

Photo Credit: Elrica Tanu

“[The benefits of exercising] is only something I found out recently because in the first three years, the symptoms were quite mild and I didn’t make any changes to my lifestyle. So that was a big mistake.”

Ms Teh Choon Ling, Centre Manager of Parkinson Society Singapore, also highlights the importance of early intervention. The organisation works with hospitals to help newly diagnosed PD patients.

“It would be best if from the start, they come for physiotherapy classes because there are times where someone comes in after five to six years and they may not have very pronounced symptoms in those years so they may just go along their daily lives as usual, on medication. Sometimes they only walk in when they really need help.”

While PD isn’t fatal, it comes in different stages and worsens with each stage.

The Parkinson Society Singapore provides support to help PwP “manage their condition better”. This comes in four categories – movement, speech, dexterity and cognitive related therapy.

Additionally, the society has a specialised support group for young PwPs called the Youthful Parkinson’s Circle.

Ms Teh says: “A lot of the younger [PwP] make enquiries on the phone but we seldom get to see them. I think it could be a stigma and they may not want their employers to know about their condition.” The centre is also only open during office hours, which may make it difficult for those working to visit.

According to a Ministry of Manpower spokesperson, under employment regulations, PwPs are protected from wrongful dismissals at work. Whether a PwP should promptly inform their employer about their illness depends if their condition affects their ability to work and the company’s policy.

Young Patients’ Dilemma

Ms Tanu regrets living in denial when she was first diagnosed.

She said she had “two choices”. The first was to redesign her life and give up her dream of being a documentary producer, director and writer. This was “an insurmountable task at that time”, as she’s in love with her exciting albeit demanding job. The other option was to go with the flow, which was what she did.

“I was 30, I would stay late and go home at 2 and 3am because my friends were doing that and I wasn’t treating myself like the sick person that I was.”

Elrica Tanu

Former Documentary Producer

Photo Credit: Elrica Tanu

The turning point when she knew she couldn’t hide anymore was when she collapsed in the office. Her immediate colleagues knew of her condition and “were really helpful in making sure that [she] stayed safe”.

But as her condition worsened, her work became increasingly difficult.

“It made it more difficult for me to not feel like I’m not a liability on set. If anyone of my team members were to come up to me and say [they had the same condition], I think I would tell them to not turn up to set and try to contribute in a more desk-bound office kind of way.”

Ms Tanu has since switched to a more desk-bound role and is glad that she can still support her company in another way.

Fortunately for her, she’s in a condition that still allows her to work. For others who lose their jobs due to PD, it can be difficult to cope financially. According to the National Council of Social Service, those who need help can approach their local social services office to seek assistance where help is provided based on their overall household financial situation.

Ms Teh recalls a young 28-year-old lady who was diagnosed with PD and wasn’t able to work anymore due to her trembling hands.

“[The lady] was crying because she just had her baby 3 months before she was diagnosed… The sad part was … she didn’t dare to hold her baby because of her [trembling] hands,” Ms Teh said.

Unlike older PwPs who have retired or are approaching retirement age, younger PwPs risk losing their livelihood and become financially dependent on others for a long time. For some, they may even lose the courage to socialise, go on dates, get married and build a family.

Ms Tanu is currently single and says it’ll be difficult to find an understanding partner.

This is one of the reasons why she doesn’t mind making her condition public. “Only ask me out if you know and you’re okay with [my condition],” she says.

She has also learnt not to let the fear of missing out affect her.

She explains: “I won’t be able to do a lot of the stuff that I used to be able to do, but I think if you focus your attention and energy on the things that you can’t do, then I think you’re missing life.”

“You’re missing out on the things that you can do, and the potential for you to do the good that you still can,” she adds.

Sharing Her Story

It took Ms Tanu five years to accept her illness and feel comfortable about sharing her story.

She reached out to people regarding her PD only recently and looking back, she wishes she’s able to face her condition more positively earlier.

“When you try to hide while it was still possible to hide, [it’s] a lot of energy and time wasted,” she said, adding that she now recognises that her health and her time are the most important things to her.

She has since started blogging about her experiences.

“Five years ago, I didn’t know anything about the disease and I had access to a lot of information but I didn’t have access to people like me.”

She explains that she didn’t have a friend who went through the same thing she did. With major health conditions, people tend to be quiet about it. “I think it would have been helpful to have someone tell me that ‘you know, you don’t have to be too afraid’.”

“The point of early detection is for you to do something about it. I was very lucky that I was diagnosed early, but I didn’t do anything. I could have done more,” she says.

Ms Tanu wants people to know that PD affects younger people too. “That’s about 10% of the people who have Parkinson’s … Even though it’s a progressive disease, you can still do something about it.”

Edited by: Hannah Fletcher

Proofread by: Christel Yan