When 66-year-old Mr Thevan visited India in 2018, he was surprised by how often people greeted him with a simple nod or a “vanakkam”. Back in Singapore, he’s rarely on the receiving end of these warm gestures.

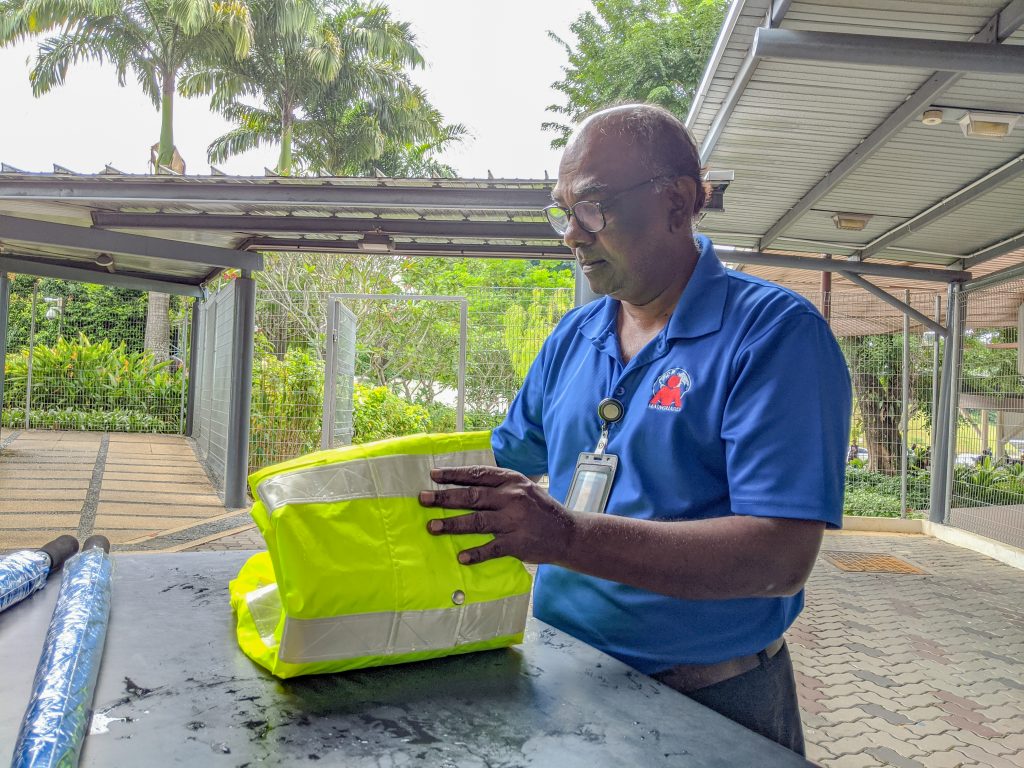

Working at Ngee Ann Polytechnic as a security officer, Mr Thevan sees many people passing through the campus gates his 12-hour shift.

While he takes pride in being the gatekeeper and warden of a 33.6ha campus with a 14,000-strong student population, he wishes that he can have more interactions with people during his long shift.

“(Sometimes) we greet people, they ignore us,” Mr Thevan sighed, blaming it on Singapore’s classist culture.

“Society hasn’t changed,” he said, adding that people like him “respect the rich” but cannot expect reciprocation since they’re not making as much money.

According to the 2018 data from the Ministry of Manpower, the median gross monthly wage of security guards is $2,225. This is higher compared to that of cleaners in the F&B sector, who make just $1,200 a month, but much lower when compared to the average of all occupations ($4,109).

On the other end of the spectrum, those in the highest income bracket such as foreign exchange dealers can command a median gross wage of $18,821 per month.

The plight of security guards in Singapore came to light after a dispute between a condo resident and the security supervisor on duty was filmed, uploaded and circulated online in October.

In the video, the resident, later revealed to be a high-ranking JP Morgan executive, is seen hurling vulgarities at the security supervisor over a rule that requires his visitor to pay $10 for using the carpark.

The incident has since cast a spotlight on the income gap between high-earning professionals and blue-collar workers, and how it’s contributed to the class divide that is increasingly acknowledged as a main faultline in Singapore.

In late October, the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) published its latest working paper, which highlights the most divisive faultlines in Singapore based on the responses of 4,015 individuals.

One of the most prominent faultlines is socioeconomic status (SES), which has “emerged over the past decade or two with Singapore’s development and economic success”, said

Mr Melvin Tay, 29, a research associate who’s contributed to the IPS study.

“Depending on how society or individuals perceive value, attitudes towards others worse off, or better off, would take root and develop,” said Mr Tay.

Another security guard, Mr S. Peruman, 73, believes that public attitude towards those in his profession is unlikely to change despite heated debate over the viral video.

“I cannot change people’s perception of security guards; it is up to people to perceive you in the way they want,” said Mr Peruman.

In contrast, Mr Tay believes perceptions can be changed, and that, in some cases, “some government or policy intervention” may help to curb negative attitudes.

Thinking beyond policies, Mr Thevan chose to place his faith in youths.

“We should start with schools,” he said. “We start with the young, and it becomes part of human life in time.”

No matter where change comes from, Mr Tay believes that the recent disputes should warrant “more societal attention” on the SES and Immigration faultlines.

“It is essential that we are cognizant of these potential fautlines and do our part to steer society away from their perils. There will be sporadic incidents that seem to feed our innate biases,” said Mr Tay.

“The keyword here though, is empathy, where we recognize that everyone has aspirations and obstacles, and seek to understand each other beyond the superficial.”